The power of language

Language is a powerful tool. I’ve written before about the value of metaphor in mental health  support and how it can reframe and change perception as well as helping people understand subjective experience. Language is also a tricky thing – the way we frame things in words can influence how we think about them and what assumptions we make about what they describe.

support and how it can reframe and change perception as well as helping people understand subjective experience. Language is also a tricky thing – the way we frame things in words can influence how we think about them and what assumptions we make about what they describe.

‘Young People in the Internet Wilderness: A Psychological Time-Bomb?

I found myself thinking a lot about language last week while at a joint Young Minds and ACAMH conference. Since appearing in my inbox, the title of the conference had intrigued me. It was called ‘Young People in the Internet Wilderness: A Psychological Time-Bomb? What CAMH professionals and service providers need to know to respond effectively’. The language used seemed to convey quite a negative view of how young people experience online spaces and I was interested to see whether this was a realistic interpretation of the conference organisers viewpoint, or just a catchy title to draw people in. As a massive advocate of online peer support, I also wondered why a workshop on the subject was called ‘Why online support is so popular and why it isn’t always bad’. Why not call it ‘The increasing popularity and benefits of online support’?.

Perhaps just me being semantically picky. I can certainly understand that accusation. Either title gets the nature of the workshop across after all and if the conference name was meant to draw people in, it certainly worked for me.

A wilderness, a jungle or an ecosystem?

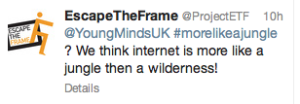

However, even before I had left the house on the morning of the conference, issues around language came up. Young Minds were looking for a hashtag for their conference. Representatives of @ProjectETF who would be speaking later suggested #morelikeajungle. They felt the internet was better described as a jungle than a wilderness. But even a jungle was considered too negative by some – an opinion perhaps influenced by the phrase ‘it’s a jungle out there’ which tends to have less than positive implications. The young people from @ProjectETF explained that they chose jungle to represent the internet because it can be fun, nourishing, interesting and new as well as containing the odd scary beast. I quite like @jarodowsky’s suggestion of the internet ecosystem. It suggests subtlety, balance, growth, evolution, interpersonal support and infinite variety.

Putting the genie back in the bottle?

The conference opened with Sue Berelowitz the Deputy Children’s Commissioner for England. She was talking about the first years findings of a two year national enquiry into child sexual exploitation in the context of gangs and groups. Her presentation was a series of pretty scary stories about the worst cases of sexual abuse of children which were facilitated by various social networks or BBM and encouraged by the easy availability of hardcore pornography online. It was sobering stuff, and there is clearly a lot of work that needs to be done to address the issues and their underlying causes. Facebook and BBM are tools that can certainly be used towards terrible ends. But it’s worth remembering that they are tools – there’s nothing intrinsically ‘bad’ about them.

One phrase she used a lot was ‘you can’t put the genie [the internet] back in the bottle’. Which suggested that if she could, she would. I can understand how someone who does the work she does and sees the cases she does might want to do this – but I was concerned that her presentation would further set the tone of the conference as;

‘How do we best manage this terrible thing called the internet?’

rather than

‘What are the benefits and risks of young peoples’ behaviour in online spaces and how can we help them get the most out of it?’.

In my experience, a lot of practitioners are very risk averse anyway when it comes to anything online (we heard throughout the day from many services how they wouldn’t get commissioned by the government if they didn’t pre moderate) and I was concerned that this kind of presentation could fuel that and make them less likely to consider offering online services to the hundreds of thousands of young people who could benefit.

The internet is just a tool

As I mentioned, one of the things I liked about the ecosystem metaphor for the internet was the implication of enormous variety. But something that struck me was many people tended to refer to ‘the internet’ as one amorphous thing – often using ‘social media’ and ‘the internet’ interchangeably. This was similarly the case when looking at bullying. While there were distinctions made between different types of ‘traditional’ bullying, any of the many types of bullying that involve some kind of technology in their implementation were all called simply ‘cyberbullying’.

Again, I felt it was important to emphasise that fundamentally ‘the internet’ is just a tool, in the same way as paper and pen is a tool, or the telephone is a tool. Similar to a pen and paper, it allows us to do an enormous range of different things in as many ways as there are people who have imagination or inclination to do so. There are dangerous ways to use it, and life changing ones – mundane ways to use it and brilliant ones. Some of these ways are damaging and illegal, others provide something immensely positive that couldn’t be found anywhere else. In many cases, the most important thing about what is created is not the fact that technology has facilitated them in some way – in the same way that the most useful thing to know about both 50 Shades of Grey and Hamlet is not that they were written on paper using a pen.

My old manager Patrick just left YouthNet, and before he went he wrote a really relevant piece about how it’s no longer about the technology alone – it’s about the relationships this technology allows you to build.

“But fundamentally, online is clearly another way for people to relate to each other, care for each other and support each other. In some situations it’s better, in others it’s limited. The web is social.”

If your understanding of ‘the internet’ is rooted in one particular way of using it, so much so that you use the word for the tool itself, and the word for one way of using it interchangeably, you are likely to make more judgements about it, and unlikely to approach it with an open mind. Of course, it’s a useful word to have in the lexicon. However, if people want to be able to support young people to navigate it and to offer them support in online spaces then they need to examine their assumptions about what they understand by ‘the internet’, explore it’s variety and realise that the tool itself is only a small part of the story.

‘Real life’ and ‘online’

There’s one final bit of semantics that I’m going to look at here. Again, I run the risk of being lambasted for pickiness – but I think the way these words are used can carry a number of assumptions.

People often use the phrase ‘real life’ to refer to experiences which take place offline – and ‘online’ to refer to interaction or behaviour using online tools. The implication here is of course that somehow interactions (of whatever nature) that take place offline are more ‘real’ and valuable than those (of whatever nature) that take place online. This seems to suggest either a lack of knowledge or understanding about how ‘real’ support or relationships facilitated by the web can be – or a rejection of this fact.

In addition, it continues to embed the idea that the most useful distinction to make is whether the support or interaction (whether negative or positive) uses the internet to facilitate it or not. I’m not saying this isn’t one distinction, but I often don’t think it is the most useful one. In addition, as young people live increasingly merged lives, I’m not sure that this is the most important distinction that they would make either.

I’ll return to Patrick’s blog;

“In fact, as these things become increasingly interwoven in how young people’s support services operate, it’s becoming less meaningful to specify online or offline, or single out a platform as a unique path to such and such an outcome.”

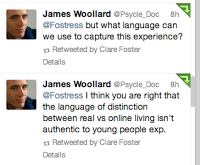

I tweeted about this distinction during the day and received a response from James Woollard  agreeing with me, but asking what language could be used instead. I would tend to use ‘offline’ or ‘face to face’ rather than ‘real life’ – but if that’s what one chooses to use, fine. For me, it’s more about being aware of the implications of the phrases as we use them.

agreeing with me, but asking what language could be used instead. I would tend to use ‘offline’ or ‘face to face’ rather than ‘real life’ – but if that’s what one chooses to use, fine. For me, it’s more about being aware of the implications of the phrases as we use them.

This is the first time I’ve explored these thoughts in detail on here, and there’s definitely a lot more to be said. I certainly don’t have a definitive position and I have a niggling feeling that some of my thoughts might still be contradictory.

Focussing on the causes, the interactions, the needs and the relationships

But perhaps as our lives become increasingly facilitated by all kinds of technology, whether an interaction with someone takes place on or offline is no longer the most important thing to say about it. It certainly doesn’t become less ‘real’ if it takes place online. If we want to talk about how the interaction is facilitated, we should use more detailed and knowledgable language than purely ‘the internet’ – as the scope for variation is enormous. And when supporting young people, whether with mental health, bullying, abuse or anything else, youth workers shouldn’t be blaming their tools or rejecting them out of hand if they see them used negatively. We should be focussing on the causes, the interactions, the needs and the relationships themselves – and, as part of our work, identifying which web based tools can be used positively to help us facilitate further support.