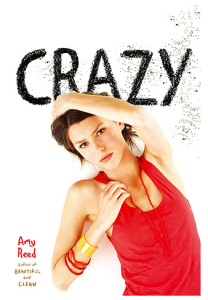

A review of Crazy by Amy Reed – published by Simon and Schuster

It’s hard to truly imagine what depression or bipolar disorder is actually like. The language of mental health is woefully inadequate. The word ‘depression’ has become part of the spectrum of everyday language used to describe feeling sad. We’ve all said or heard it. “My team lost, I’m so depressed” or “God, this TV programme is so depressing”. As a result it becomes harder to find the words to adequately distinguish between natural sadness and the entirely different experience of a chemically depressed mind.

Someone without diagnosed depression might fail to understand why those who have can’t ‘just cheer up’. Those who are ill might judge themselves a failure for feeling unnaturally sad or incapable. A greater linguistic distinction would be helpful.

But even if the words depression, mania, OCD or psychosis were only ever used to describe specific conditions, they still don’t explain what it actually feels like. That’s where stories can play an important role.

Reed’s ‘Crazy’ is one of those stories. It explores a mental health crisis through the eyes of those experiencing it. Told in a modern epistolary style through emails and instant messages between two teenagers, it has an immediacy and deeply personal feel that works well with the subject matter. After meeting at camp, Izzy and Connor start exchanging emails and chatting online. It soon becomes clear that something isn’t right. Izzy’s highs are too high and her lows are scary and dangerous.

Mental illnesses often display initial symptoms during the notoriously chaotic teenage years. This confusion is reflected in the questions they ask each other about who they are and what their lives mean. The lack of an external narrator means that readers also feel the uncertainty of each emotion. Our understanding of the situation develops alongside theirs. We’re not just being told about the misinterpretation, distrust and anger that so often go alongside Izzy’s condition, we’re experiencing it too.

We get upset alongside Connor when she hurts him

‘Just because you can’t figure me out doesn’t mean I’m crazy. What the hell is wrong with you?’

We see things from Izzy’s perspective when she feels guilty for losing control.

‘I’m sorry I got so mad. Can you swoop down and save me from all the crazy thoughts in my head?’

We ask the questions they ask; is there something wrong or do all teenagers feel this way? For much of the book we’re not sure. Izzy and Connor are unreliable narrators after all. How are they representing their lives to each other?

We’re not given much help. The language is very informal and the structure, right down to the time stamps on the emails and instant messages, feels stilted. We might be voyeurs sneaking a look at a messy teenage love affair rather than readers in the safe hands of an author with a plan. This is sparse and challenging reading.

Unfortunately, as we reach the final chapters, we suddenly see Reed’s plan in plain sight. The novel builds to a tense and terrifying crisis point and then just tails off.

All epistolary literature involves some suspension of disbelief. Would the character be recording dialogue in such detail? Would they be describing such a dramatic situation in their journal almost as it happened? Why is Bridget Jones writing her diary rather than looking after her sick child? As fans of Fielding’s Bridget will know, these questions are unimportant if the story keeps us interested.

In the first two thirds of ‘Crazy’ Reed keeps us gripped. It’s very believable. The dialogue is reported but realistic. These teenagers don’t craft poetic accounts of their surroundings for our benefit – we’re left to imagine most of that for ourselves. Even the conceit that Izzy doesn’t like talking on the phone is one that many people who have experienced depression and anxiety could relate to. But in the final third it’s not just Izzy who comes apart.

Reed has said she wanted readers to be inspired to access help but as a result the end feels very forced. We no longer believe Izzy is writing to Connor. Instead we see the author writing to her teenage readers in the manner of a suicide prevention scheme.

There are many ways in which this novel is a success. The comments on Reed’s website suggest it has encouraged many young people to access help. If you’ve experienced depression or bipolar disorder then ‘Crazy’ could certainly help you see you’re not alone. If you haven’t, it could help you understand.

If only the ending were subtler. As it is, to appreciate ‘Crazy’ you need to recognise how much it does do well, value the positive impact it’s clearly had, and forgive the fact that the final chapters are rather more support service than story.